Kiva Gallery loves Nicholas Galanin and thinks he is one of the most important figures in contemporary art, so we are excited to hear that Heard Museum will host a mid-career retrospective of his work. The exhibition will be titled ”Dear Listener” and run through May 04 to September 03, 2018. To my knowledge it will the biggest solo exhibition of Galanin’s work to date and will encompass more than 10,000 square feet of new and existing works by Galanin including video installation, sculpture, performance art, works on paper, installation work, and fashion.

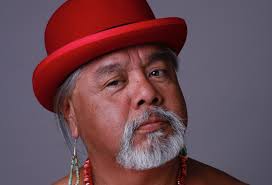

A few words in remembrance of James Luna and his artistic fearlessness.

The world of performance art suffered a great loss when artist James Luna passed away at the beginning of this month. A resident of the La Jolla reservation, Luna was a highly respected figure of the California Native community. As someone who considers La Jolla and its surroundings somewhat of a second home, I have seen first hand how revered and admired Luna is in those parts. His importance, however, transcends geography and his work has been particularly relevant to recent discussions of cultural misrepresentation and appropriation. With a president who casually refers to his Native American co-workers as “Pocahontas”, the current political climate needs every strong voice of objection and protest it can summon. Luna was indeed one such voice and many of his pieces were conceived to actively disrupt the romanticized commodification of Native culture. In the performance “Take a Picture With a Real Indian”, for instance, Luna targets the gap between the popular image of Indians and Indians as actual human beings.

Luna originally staged the performance at Union Station in Washington D.C. in 1991. The performance consisted of Luna taking up a spot and proclaiming to bypassers: “Take a picture with a real Indian. Take a picture here, in Washington, D.C. on this beautiful Monday morning, on this holiday called Columbus Day. America loves to say ‘her Indians.’ America loves to see us dance for them. America likes our arts and crafts. America likes to name cars and trucks after our tribes. Take a picture with a real Indian. Take a picture here today, on this sunny day here in Washington, D.C.”

Being photographed together with strangers who saw him primarily as an object would not surprisingly take a toll on his pride and Luna would end the performance when he felt too upset or humiliated to continue.

The video above is from a more recent recreation of the performance but here too the discomfort is clearly visible. This discomfort seem to be shared by performer and participants alike. Sometimes it’s unclear why the people in the audience want to have their picture taken together with Luna. Are they clued into the motives behind the performance or do they respond to the exotic nature of the offer, as if being photographed with an Indian is an opportunity as rare as meeting a lion. Maybe the participants themselves don’t really know. And this confusion and uncertainty is testament to the success of the work. The performance opens a space for the audience to question their own reception of exotic constructs.

Luna was reportedly trained by the mythical Bas Jan Ader who disappeared at sea during the creation of one of his art pieces. Although he didn’t go to quite the same extremes as Ader, Luna did make his own body his primary artistic medium. This made Luna’s work particularly challenging. Other Native artists may have tackled the same subjects as Luna, but the fact that he used his own body lends an confrontational and physical poignancy to topics and themes that might otherwise remain confined to the intellectual realm.

Luna’s physical methods were particularly effective when he located his critique to the institutional practices of museums. In “The Artifact Piece” (performed in 1987 at the San Diego Museum of Man) Luna put his own body on display, laying it down in the museum among other historical objects. Thinking he was a lifeless object of exhibition, some visitors would touch his body and experience a slight shock upon finding it a living and breathing entity. It is one thing to verbally point out the discrepancies between the Native American as historical artifact found in museums and Native American as a living and thriving culture. But to stage this discrepancy through one’s own body is quite another thing and the piece had a huge impact among Native artistic communities.

Personally, I knew James Luna only very superficially. A few years ago James Luna reached out to me with the proposition of collaborating on something in Sweden. Nothing materialized, however, and I sadly regret that the opportunity now has passed. Among many of the artists represented by Kiva Gallery, James Luna is spoken of with the highest admiration and respect. Luna struck a rare balance of fearlessness, humour and sensitivity in his art, and for this his influence will doubtlessly live on.

2018 – the year of the Native American blockbuster?

“Now I think more and more people are becoming involved and beginning to make films with their own ideas. We’re just looking for the first big crossover film that is Native American-themed and written and produced and everything.”

-Wes Studi

It’s a new year and a time for looking ahead. So let’s start the new year off on a hopeful note. This interview with actor Wes Studi will put you there. Studi is such a veteran that it is a surprise for me to learn that he didn’t really start acting until in his 40s. His big break came quite fast in the role as The Toughest Pawnee in Dances With Wolves (1990). Since then Studi has put over 90 credits to his name. He’s played a lot of Indians of course but also more non-ethnic specific roles, such as detective Casals alongside Al Pacino in Heat. Studi still yearns to be known as just an actor rather than a Native American actor and dreams about helming a comedy about a grumpy old man. A Native American in a leading role that is not defined primarily in Native American terms would indeed be a game-changer.

And who knows. Having recently watched the amazing Wind River (which I will write more about in a few days) I’m at moment hopeful about the future of Hollywood. The clean-up currently going on in the movie industry can only pave the way for a new Hollywood, one that’s hopefully more diversified and open to all kinds of narratives, not just ones that appeal to old white men.

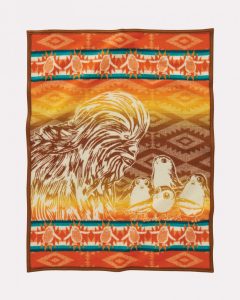

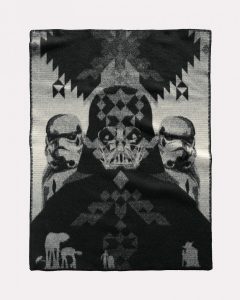

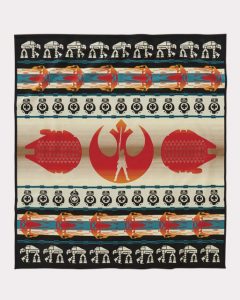

Pendleton has made the perfect accessory for your next visit to the ice planet Hoth

Oh wow! Didn’t know this existed. The textile manufacturing company Pendleton has released a series of Star Wars blankets. Luke Skywalker and fam meet the tribes as familiar Star Wars motifs are set against backgrounds of traditional Native patterns. We’ve written about the popularity of the Star Wars franchise among contemporary Native American artists. My guess is that these blankets are at the top of these artists christmas wish lists.

Pendleton has produced one unique blanket for each movie in the latest trilogy, as well as a couple of others. My favourite blanket is probably the one that accompanies Star Wars: The Last Jedi, which premiered just last week. It has a beautiful red, blue, black and white color scheme and incorporates the Star Wars iconography into the overall Native pattern.

Pendleton has produced one unique blanket for each movie in the latest trilogy, as well as a couple of others. My favourite blanket is probably the one that accompanies Star Wars: The Last Jedi, which premiered just last week. It has a beautiful red, blue, black and white color scheme and incorporates the Star Wars iconography into the overall Native pattern.

Sadly, Kiva Gallery doesn’t stock Pendleton Star Wars blankets just yet, but we do have several other Pendleton blankets for sale. Swedish winter may not be as gruelling as on Hoth, but almost. A Pendleton blanket is the perfect christmas gift, it will keep you warm and cozy all through winter.

How contemporary Native American artists counter cultural appropriation with artistic appropriation

Google “Native American appropriation art” and the first five pages of results or so are all about negative cases of cultural appropriation. On these pages we can read about how outsiders misuse Native American images and cultural heritage, such as the infamous feathered headdress on a lingerie clad model in a Victoria’s Secret show five years ago. Cultural appropriation, of course, continues to be a problem and something that should be addressed and discussed. However, when typing in that search term I wasn’t looking for Native Americans as victims. I wanted to read about how appropriation is used as a strategy within contemporary Native American art. I was looking for Native American artists as agents of empowerment. To find such results buried under droves of articles about how Native American iconography has been mistreated must feel like a double slap in the face. First whites steal Native cultural practices and use it in a distorted way, then this act of appropriation steals the attention away from Native artists who use appropriation as a way to symbolically fight back.

This makes it very difficult to place the aesthetic tactics of many Native American artists into proper art historical perspective, which is a shame, especially considering how significant appropriation is for many Native artists. Appropriation is, after all, a genre of contemporary art that has perhaps been the most important hub for questions concerning artistic authorship and originality and the contextual relativity of the meaning of images. It is perhaps within the Native art community that the legacy of appropriation art today finds it’s firmest stronghold. At first sight it may come as a surprise to learn how popular Andy Warhol is in this community. I can tell you that it is not because of his “Cowboy and Indian series”, but rather because of how Warhol demonstrated that the specialness of a sign – for instance a Campbell’s soup can – can be emptied by the act of repetition and how the meaning of a pre-existing image or object can be altered by placing it within a new context.

Warhol himself was not a particularly political figure, but the strategy of appropriation, of “copying” images and making them your own, has a history of political uses.

Dara Birnbaum and Sherrie Levine used appropriation to feminist ends. By repeating and recontextualizing imagery by male originators they questioned the authenticity of representations of gender. Appropriation has also been employed to question the commodity value of art and its underlying economic structures.

Even before it was a genre of art, Raphael Montanez Ortiz performed a case of appropriation aimed at exposing the misrepresentation of Native Americans. In 1957 he used a Tomahawk to chop up Anthony Mann’s western Winchester ’73. He then put the pieces back together at random, resulting in a complete scrambling and disruption of the original narrative. “Ortiz considered his shaman-like process resonant with his indigenous heritage. His destructive act also criticized media depictions of Native Americans.”

As a genre, Native American appropriation art comes across as something self-evident and completely natural. Artists are simply taking images back that were stolen from them. Artists such as Douglas Miles, Jaque Fragua, Steven Paul Judd, Ryan Singer, among many others, consider appropriation a way to take repossession of images that they have lost control over. In short, one might say that appropriation art is a means to combat cultural appropriation.

We’ve written about the importance of graffiti for contemporary Native artists many times here on the blog. In the hands of Native artists, painting with spray cans in public spaces is no petty act of vandalism but a profoundly political gesture. This is clearly demonstrated by Jaques Fragua who wrote “This Is Indian Land” in giant letters on a construction site in Downtown Los Angeles. The act of appropriation is performed in a spirit kindred to graffiti. For Native American artists it is about re-claiming what is rightfully theirs by symbolically taking back their land by illegally writing on it, or redefining images that have been made from an external point of view.

We haven’t written about Jaque Fragua on the blog before, so let’s continue on him. Besides graffiti, Fragua considers appropriation one of his artistic go-to’s. “The Big Chief” is for instance a commercial symbol that has become a recurring character throughout Fragua’s work. Fragua explains: “He’s a chief from a sign that’s near my reservation, at Big Chief Gas Station. If you’ve ever watched Breaking Bad, you’ve see that gas station. I lifted him and I’ve been putting him everywhere—he’s the Big Chief, right? When you put a mirror against another mirror, you start seeing the core of the truths.”

In another interview, Fragua explains the appeal of appropriation more in depth: ”Simply, it’s about imagery that continues to colonize us. By creating fine art out of these visuals and emphasizing the images ad nauseum, it creates the opposite effect. Sort of like Warhol’s soup cans.” Fragua thus reappropriates his culture’s iconography in a way that conceptually subverts our overconsumption of misappropriated Native American images that has turned into stereotypes.

Some critics fear that appropriation as a artistic gesture has lost some of its meaning in a time when borrowing, quoting, stealing and copying is everyday practice to the point of being ubiquitous. However, for Native American artists, appropriation simply follows the rules of the game set by a white hegemony. It is the answer to a signifying practice already put in place. As such, appropriation is important now perhaps more than ever. With a president that casually refers to people of Native American heritage as “Pocahontas”, and a culture at large that hold it’s racial stereotypes dearly, appropriation as artistic weapon offers a way to strike back. Contemporary Native American artists turn to appropriation not to be trendy or edgy but out of urgency. It opens a line of dialogue that lets Native Americans have the last word on images that they were not in charge of in the first place and thus to let the public know what they think about them.

Further reading about cultural appropriation:

https://unsettlingamerica.wordpress.com/2011/09/16/cultural-appreciation-or-cultural-appropriation/

https://jezebel.com/5959698/a-much-needed-primer-on-cultural-appropriation

http://nativeappropriations.com

About appropriation art:

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-the-art-of-copying-ten-masters-of-appropriation

https://www.thoughtco.com/appropriation-appropriation-art-183190

“Okay, I think I can do that”: How to look at art and get inspired to do, well, just about anything.

There are days when you don’t have anything in particular to report – no news and no opinions. Some days you just want to write about something that makes you feel good. Something to inspire you to get off your ass and do stuff. Something in the “hell yeah!”-vein, in other words. This is one of those days. There are many things I love about Native American Art, but there is one thing in particular that keeps hold on me and it’s something that runs deeper than surface aesthetics. It is a certain attitude that shows you how powerful art can be. Art can give you a voice when other means of expression are suppressed. It is hard to find that attitude elsewhere, at least so collectively concentrated. The realization that art can show reality but also create another reality is what makes so many Native communities bubble with creativity.

The rapper Drake said in the song “Fireworks”: “from the concrete who knew that a flower would grow”, meaning that it is surprising that beauty could come from harsh circumstances. He clearly has no concept of Native Art. Or, to take an example closer to Drake’s own rap identity – New York’s graffiti culture in the late 1970s and early 80s. There is a lot about that era that reminds me of the contemporary Native art scene. That period is all about the creative ways of the disenfranchised to grow out of the concrete. Spraycan graffiti was a completely invented art form so there were no art schools to teach you how to do it. Ghetto kids were the professors and their education was on the streets where the tricks of the trade were passed from peer to peer. At the beginning there were no commercial ambitions- the practitioners had yet to find a way to monetize their art. It was just about rising above the everyday struggle by creating something beautiful and spreading it throughout the streets.

Art is empowering. It let’s you create and define your own world. When the realization of this occurs on a collective level, like with graffiti in 1970s New York, art is injected with an energy and enthusiasm that is highly intoxicating and convincing. Similarly, a lot of Native Americans today latch on to art as a source of optimism and tool for change.

I’m writing these words with one particular artist in mind: Steven Paul Judd. Few people embodies the DIY – attitude like Judd. He embarked on his artistic trajectory when trying to find some nice Native art to hang in his house. He failed to find anything that corresponded to his taste for pop art, so he simply set to work making some himself.

It is no accident that Judd has close ties to graffiti culture. But labelling Judd just a graffiti artist would be reductive. Creativity just pours out of him and into every facet and category of art. This guy is just pure inspiration, in the truest sense of the word. He has no proper education in the arts so he doesn’t always know the ”hows”, he just knows that he has to do it. And a lot of the times, Youtube tutorials will get you where you need to go. The quote in the title to this piece, of course, comes from Steven Paul Judd. And the mentality of going for it runs through his entire practice of art.

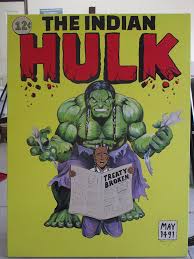

Not least it applies to his approach to historical iconography. Judd quite often uses familiar imagery but in a way as to make it more Native-centric. He uses art to create his own alternate version of pop-culture, for instance by fusing historical Native American iconography with the world of Star Wars, or by recasting superheroes such as The Hulk as Native American. Claiming your space in this way, despite what history and the powers that be say, is a deeply graffiti-like attitude.

In an interview Judd talks about his creative process in a way that seems to be representative of his energy and eagerness to get things done. Recently, Judd has been creating portraits of Sitting Bull, composed entirely out of Rubik’s Cubes. Which is like building a complicated puzzle, with smaller puzzles for pieces. The initial plan was to mount it on the wall but he finished the puzzle before he had figured out a way to fasten the cubes on the wall. So he just let the cubes lay on the floor, the art work now an installation rather than a wall piece.

If there’s a will there’s a way, I believe is the accurate motivational phrase here.

To continue in this vein of self-improvement, let us sum up by making it a rule that whenever you feel that things are just too damn hard, ask yourself: what would Steven Paul Judd do? If the conclusion you come up with is not “Okay, I think I can do that”, you’re doing it wrong.

Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World

The 28th edition of Stockholm International Film Festival starts tomorrow and there is one film in particular I would really like to see. It is a documentary called “Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World”. The film explores the contribution of Native Americans to the evolution and history of rock and roll. As is evidenced by the many accounts from Rock and Roll superstars in the film, such as Steve van Zandt, Steven Tyler and Iggy Pop, Native American rock has had a significant influence on many popular musicians. Rarely has this influence been spelled out as specifically Indian, however, or contextualized in a coherent story about Native Americanness. The idea for the film came from Native American Stevie Salas who has himself been a professional musician for decades and played for many for big names. He knew the industry was full of Indians who were really influential but that not many people knew about outside the industry. For four years the filmmakers collected accounts from Native American musicians and other artists who had one way or another been influenced by rock by Native Americans.

Many of the rockers interviewed for the film talk about one track in particular: Link Wray’s Rumble from 1958. The track has a riff that Stevie Van Zandt calls “The Sexiest, toughest chord change in all of Rock and Roll”. In that chord change lay the foundation to the history of Rock and Roll and one can easily trace it through the sound of The Who, Black Sabbath, Stooges among countless others.

To get an idea of the monumental impact of the track you only need to watch as Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page puts it on and gets so overcome by its power that he cannot refrain from busting out some air riffs along to it.

Rumble has had a pop-cultural impact that stretches beyond the world of music. Film buffs may remember Wray’s tune as an indispensable addition to the mood of Pulp Fiction. The song appears during the famous (well, aren’t pretty much all scenes from Pulp Fiction famous) diner scene during which John Travolta and Uma Thurman have their “uncomfortable silence”. Since the dialogue is here put on hold for a large part the music is what primarily carries the scene.

“Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked The World” is directed by Catherine Bainbridge and Alfonso Maiorana and has earned numerous awards from other film festivals. Tomorrow November 8, it can be seen at Stockholm Film Festival at 7 pm. There are additional screenings on November 12 and 16.

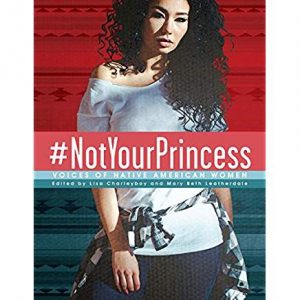

#NotYourPrincess

“It’s strange to me how people always want me to be an “authentic Indian.” When I say I’m Haudenosaunee, they want me to look a certain way. Act a certain way. They’re disappointed when what they get is . . . just me. White-faced, red-haired. They spent hundreds of years trying to assimilate my ancestors, trying to create Indians who could blend in like me. But now they don’t want me either. I’m not Indian enough.”

“It’s strange to me how people always want me to be an “authentic Indian.” When I say I’m Haudenosaunee, they want me to look a certain way. Act a certain way. They’re disappointed when what they get is . . . just me. White-faced, red-haired. They spent hundreds of years trying to assimilate my ancestors, trying to create Indians who could blend in like me. But now they don’t want me either. I’m not Indian enough.”

“The Invisible Indians,” Shelby Lisk

The above is a quote from a new anthology titled #NotYourPrincess: Voices of Native American Women, by Charleyboy and Leatherdale, eds. I’ve only sampled sections from the book so far but it looks like a good and perhaps important read.

The book addresses the prejudices and expectations faced by native women, especially young women. Purposefully eclectic and sprawling, it tries to show the diversity and complexity of native female identity. It does so through form as well as content. Poetry here sits next to scholarly writing, illustrations and graphic design. The whole experience of the book seems to be perfectly in tune with digital identity. The anthology quotes from Twitter and one chapter adopts the layout of Instagram which should please a younger readership who is as much, perhaps more, at ease with social media than conventional books.

I’m definitely putting the book on my “to-read” list and you will probably see more about it here on the blog in the future.

We the People

A lot of the issues, artists and news that have been covered on the blog this past spring and summer have now been collected in an exhibition at the Minnesota Museum of American Art. Called “We The People”, the exhibition investigates just what constitutes the American nation, and who are being excluded, at this point in history. It’s not just about the Native American experience but it is a big part of it. Among the Native American subjects that are tackled are Standing Rock, cultural appropriation and social consciousness in general.

Any believable approach to contemporary identity has to include the digital realm. Some of the work included in the exhibition seem to directly concern art’s relation to social media. For those thirsting for information, there is a lot to be found on the internet. But the tempo on social media is dizzying fast and one thing, or hashtag, is quickly replaced by another. Can art interface with this rapidity or is it doomed to always be one step behind? The exhibition offers two answers from two different art works. Marlena Myles’ “Dakota 38 + 2 Prayer Horse” is technically and aesthetically a very pleasing piece of work. But thematically it seems to arrive too late. Myles has taken the controversy of Sam Durant’s planned sculpture “Scaffold” at Minneapolis Sculpture Park as her subject. But as the conflict has already been elegantly resolved the painting has turned sadly obsolete and irrelevant.

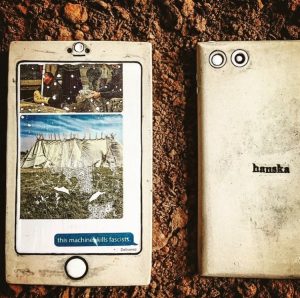

Cannupa Hanska has another approach. He was a notable presence at the protests at Standing Rock and his “The Weapon Is Sharing (This Machine Kills Fascists)” (2017) follows up on those protests. Like Myles’ painting this is thus a highly topical work but it manages to transcend the specific to make a comment on the nature of digital documentation in general. Hanska has recreated cellphones out of clay and printed photographs from the protests at Standing Rock onto them. He thereby gives them permanence beyond the momentary and ephemeral. At the same time, the mimicking of historical artefacts will infiltrate the archives with a narrative of resistance and protest. Cannupa Hanska’s eloquent explanation is worth quoting:

The exhibition is curated by four people with different backgrounds, and besides a strong Native presence the curators weigh heavily on LGBTQ themes, and issues of African American identities.

It seems like an important exhibition and I wish I could visit but it’s a little off the beaten path for me.

The exhibition runs August 17 – October 29, 2017.

Different times.

Buffy Sainte Marie said of her experience working on Sesame Street that it was ”Wonderful all around. I was on for over five years (until Reagan cut the budget for the arts). We took Big Bird to Taos Pueblo, did multicultural programming in my backyard in Hawaii, and lots in New York. They never stereotyped me, always listened to my script ideas, and stayed truly child-centered. I was breastfeeding my baby in 1976 and suggested we do a segment on it, and we did and it was perfect. (We) also did sibling rivalry, and I taught the Count to count in Cree. As a songwriter who really believes in the power of the three-minute song to change the world for short-attention-span audiences, ”Sesame Street” was right up my alley, and I’m grateful for every minute of it.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65AdU7w-Hg4&t=33s