Wendy Red Star is one of the most exciting contemporary artists at the moment. There was recently a feature article in Vogue about Red Star which is a clear sign that she is hot stuff in the art world right now. Moreover, she has a solo exhibition at Newark Museum. It is an extensive exhibition that covers her production from 2006 to 2019 and includes more than 40 of her works.

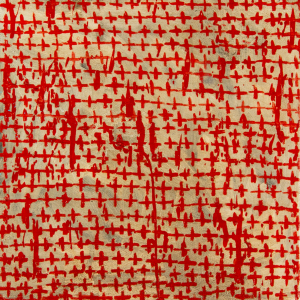

Red Star has tried her hand at many different mediums. Some, such as weaving, she uses because of it’s traditional link to the crafts of her reservation – the Apsáalooke (Crow) in Montana. But it is perhaps her photographic work that has drawn the most attention. Red Star often uses herself as subject and model in her photographs.

A recurring theme for Red Star’s art is the politics of identity and memory.

Many of Red Star’s works utilize strategies and methods found in conceptual art. “My Home is Where my Tipi Sits”, for instance, echoes Bernt and Hilla Becher’s photographic typologies. But a still more significant influence is arguably the “theatrical” trend in 1980s art. The staged quality of Red Star’s work can be traced back to artists such as Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons, Robert Longo, Richard Prince.

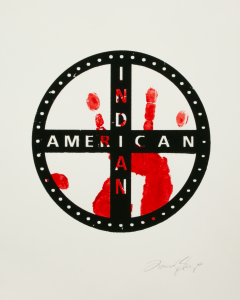

These artists used strategies of theatricality and artifice to explore the manufactured nature of various identities. As does Red Star. But when she employs similar strategies she needs them to convince more than the artists above. That’s because the figure of the Native American is arguably surrounded by some of the most rigid stereotypes there are. In the series “Four Seasons” (2006) Red Star examines and seeks to undermine the image of “the natural Indian” – a Native American with a privileged bond to nature and to earth. As evidenced by Disney’s Pocahontas, the illustration for the butter Land o’Lakes and countless posters, album covers and posed photographs, there is such a shortage of Native American artists and cultural commentators with a strong voice on the international stage, that these stereotypes are often allowed to continue to shackle Native identity. Many whites hold their stereotypical notions dear and are profoundly invested in the view of the Native American as holder of the secrets to nature.

These artists used strategies of theatricality and artifice to explore the manufactured nature of various identities. As does Red Star. But when she employs similar strategies she needs them to convince more than the artists above. That’s because the figure of the Native American is arguably surrounded by some of the most rigid stereotypes there are. In the series “Four Seasons” (2006) Red Star examines and seeks to undermine the image of “the natural Indian” – a Native American with a privileged bond to nature and to earth. As evidenced by Disney’s Pocahontas, the illustration for the butter Land o’Lakes and countless posters, album covers and posed photographs, there is such a shortage of Native American artists and cultural commentators with a strong voice on the international stage, that these stereotypes are often allowed to continue to shackle Native identity. Many whites hold their stereotypical notions dear and are profoundly invested in the view of the Native American as holder of the secrets to nature.

As Daniel Larkin explains:

What is particularly brilliant about Red Star’s photographs is that they look better than they actually are. What I mean is that, at first the images appear to unproblematically play into the hands of those with romanticized notions of Native Americans. What the viewer initially encounters is an adorned Native woman in a beautiful landscape, accompanied by animals. The image is so familiar and normalized that it is understandable if the viewer does not immediately spot the ”tells” that this image is fake, such as the suspicious creases in the landscape – which is actually a poster – behind Red Star. Or the blatant two-dimensionslity of the cardboard animals. Through this perceptual twist, Red Star’s images not only uncovers the artifice of visual clichés but also lay bare the viewer’s willingness to be seduced by them.

Red Star’s staged photographs remind me a bit of that scene in Night at the Museum where Ben Stiller tries to have a conversation with Sacagawea through thick glass that mutes all sound. Red Star’s tableau’s are similarly characterized by disrupted communication. That Red Star now has a major exhibition in a big museum is fitting considering that museums and cultural institutions have often been major agents in perpetuating skewed ideas about Native Americans.

Wendy Red Star´s mid career survey is on view at the Newark Museum until June 16, 2019

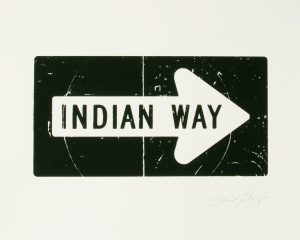

Patrick Dean Hubbell is a relatively young artist but his art feels mature. That’s a pretty cliché way to start an exposé of an artist you actually admire. Might even be a bit belittling. Sorry Patrick Dean Hubbell, I’m not good at intros! What I mean to say is that a lot of thought and consideration seems to have gone into Dean Hubbell’s art. I respect that. Now, to get through this introduction as smoothly as possible, let’s stick to some facts. Patrick Dean Hubbell is Navajo. He graduated art school 2010. He lives and works on the Navajo Nation in Window Rock, Arizona.

Patrick Dean Hubbell is a relatively young artist but his art feels mature. That’s a pretty cliché way to start an exposé of an artist you actually admire. Might even be a bit belittling. Sorry Patrick Dean Hubbell, I’m not good at intros! What I mean to say is that a lot of thought and consideration seems to have gone into Dean Hubbell’s art. I respect that. Now, to get through this introduction as smoothly as possible, let’s stick to some facts. Patrick Dean Hubbell is Navajo. He graduated art school 2010. He lives and works on the Navajo Nation in Window Rock, Arizona.

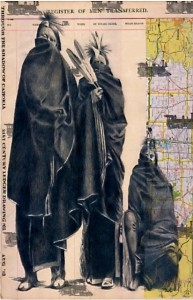

The series “Almost a Portrait” consists of obfuscated figures. They can be identified as Native American from their ceremonial clothing and other traditional markers of Native identity. Dean Hubbell states that the paintings are based on traditional portraiture and how those practices were seldom “in the best interest of” Native American peoples. There is indeed something “off” about these images. This impression is further supported by their “bad framing”. The framing makes it appear as if these were pictures taken by accident, as when the shutter goes off in between changing camera position. French film theorists referred to such “badly” composed images as “decadrage” which roughly translates as “deframing”. Some New Wave filmmakers consciously used deframed images as a way to make the spectator aware of the frame and more generally to reflect upon the constructed nature of representation. It functions similarly in “Almost a Portrait”. By literally pushing subjects out of the frame, these images signal that proper representation is not to be found here and that the truth lies elsewhere.

The series “Almost a Portrait” consists of obfuscated figures. They can be identified as Native American from their ceremonial clothing and other traditional markers of Native identity. Dean Hubbell states that the paintings are based on traditional portraiture and how those practices were seldom “in the best interest of” Native American peoples. There is indeed something “off” about these images. This impression is further supported by their “bad framing”. The framing makes it appear as if these were pictures taken by accident, as when the shutter goes off in between changing camera position. French film theorists referred to such “badly” composed images as “decadrage” which roughly translates as “deframing”. Some New Wave filmmakers consciously used deframed images as a way to make the spectator aware of the frame and more generally to reflect upon the constructed nature of representation. It functions similarly in “Almost a Portrait”. By literally pushing subjects out of the frame, these images signal that proper representation is not to be found here and that the truth lies elsewhere.

Kiva Gallery also has another Ryan Singer painting with an unusually serene mood. It is a deceptively simple scene. But if you allow it, the outline will tell a deeper story about time and stasis, tradition and generational renewal. Again, it’s a painting of a woman in a landscape. In contrast to the woman above, this woman is young. Her activity, however, is old. She is spinning wool. The landscape around her seems to respond to her activity because it curves around the girl almost to envelope her. But there is that thick outline again, tracing the contours of the girl’s body and shielding her off from her surroundings. It is almost as if the landscape is moving more than she is. A strong outline reifies movement rather than capture it. In a way it stops movement and freezes it which makes the experience of superhero comics, which are of course full of movement, deliciously paradoxical. The girl spinning wool seems remarkably still despite being caught mid-motion. From the perspective of her activity, time has stopped moving. The girl probably learned how to spin wool from her mother, and she in turn will teach her daughter. The activity doesn’t belong to her, she belongs to the activity that has existed before her and will continue to exist long after she is gone.

Kiva Gallery also has another Ryan Singer painting with an unusually serene mood. It is a deceptively simple scene. But if you allow it, the outline will tell a deeper story about time and stasis, tradition and generational renewal. Again, it’s a painting of a woman in a landscape. In contrast to the woman above, this woman is young. Her activity, however, is old. She is spinning wool. The landscape around her seems to respond to her activity because it curves around the girl almost to envelope her. But there is that thick outline again, tracing the contours of the girl’s body and shielding her off from her surroundings. It is almost as if the landscape is moving more than she is. A strong outline reifies movement rather than capture it. In a way it stops movement and freezes it which makes the experience of superhero comics, which are of course full of movement, deliciously paradoxical. The girl spinning wool seems remarkably still despite being caught mid-motion. From the perspective of her activity, time has stopped moving. The girl probably learned how to spin wool from her mother, and she in turn will teach her daughter. The activity doesn’t belong to her, she belongs to the activity that has existed before her and will continue to exist long after she is gone.