If I say Ralph Lauren the image will very likely pop into your head of a bratty young white guy, probably belonging to a fraternity at an ivy league university where he spends his family-money-subsidized days making up beer-fueled plans to rule the world, all the while sporting the polo shirt that has become synonymous with the brand. Pretty soulless, in other words. But Ralph Lauren is more, much more. He has a passion for the look and feel of the historical America that runs far deeper than what trends are advocated by the current season of fashion. Lauren has employees whose sole job is to scour through the country for forgotten artifacts and clothes to serve as the inspiration for his vintage RRL line. The resulting designs will end up in stores that resemble trading posts more than those of a high-end fashion designer.

If I say Ralph Lauren the image will very likely pop into your head of a bratty young white guy, probably belonging to a fraternity at an ivy league university where he spends his family-money-subsidized days making up beer-fueled plans to rule the world, all the while sporting the polo shirt that has become synonymous with the brand. Pretty soulless, in other words. But Ralph Lauren is more, much more. He has a passion for the look and feel of the historical America that runs far deeper than what trends are advocated by the current season of fashion. Lauren has employees whose sole job is to scour through the country for forgotten artifacts and clothes to serve as the inspiration for his vintage RRL line. The resulting designs will end up in stores that resemble trading posts more than those of a high-end fashion designer.

Lauren has a particular affinity for Navajo patterns and ever since the Santa Fe collection in 1981 they have been a recurring motif in his designs. Where other designers might treat the Indian element as an exotic and temporary flourish that is swept away as soon as the wind of trends turn, Lauren has throughout the years remained true to the style. Such dedication, however, has both its up- and its downsides. On the one hand, he is opening up new markets for indigenous design traditions, and with that hopefully raising interest in their cultures. On the other hand, the critics knock him for being an outsider that engages with Native culture in a superficial and diluted manner.

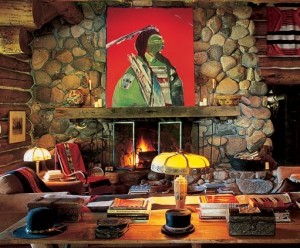

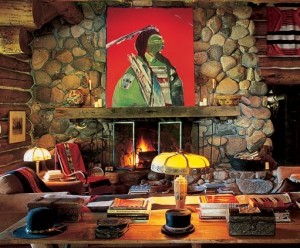

To be fair to Lauren, he always made it clear that his was a romanticized version of the old west. He began incorporating tributes to the southwest through his Polo Western collection before ever having set foot in it. Accordingly, his “vintage” line RRL and his “Navajo” designs should be taken to heart with a healthy dose of fiction. It is not for nothing that John Wayne’s hat decorates one

To be fair to Lauren, he always made it clear that his was a romanticized version of the old west. He began incorporating tributes to the southwest through his Polo Western collection before ever having set foot in it. Accordingly, his “vintage” line RRL and his “Navajo” designs should be taken to heart with a healthy dose of fiction. It is not for nothing that John Wayne’s hat decorates one  of the coffee tables on Lauren’s ranch, and his vintage collections similarly have the feel of old movie costumes more than historically authentic pieces of clothing. Still, it is understandable that Lauren’s appropriation of Native patterns and imagery might provoke hostility. Lauren’s pieces, however lovingly designed, are mass-produced and hence can never replace or even approximate the experience of genuine Navajo weaving. Behind a real Navajo textile stands a real person, and her labor and sweat is woven into the warps and wefts of the fabric. It is the reality of this person – her history and culture as well as her individuality – that is pushed to the side when the copy is allowed to stand in for the original.

of the coffee tables on Lauren’s ranch, and his vintage collections similarly have the feel of old movie costumes more than historically authentic pieces of clothing. Still, it is understandable that Lauren’s appropriation of Native patterns and imagery might provoke hostility. Lauren’s pieces, however lovingly designed, are mass-produced and hence can never replace or even approximate the experience of genuine Navajo weaving. Behind a real Navajo textile stands a real person, and her labor and sweat is woven into the warps and wefts of the fabric. It is the reality of this person – her history and culture as well as her individuality – that is pushed to the side when the copy is allowed to stand in for the original.

Besides, one can’t help but think that if Lauren really wanted to pay more than lip service to Indian culture, he would at least include some Native people in his campaigns or on his runways.

For real deal Navajo weaving, drop by Kiva Gallery’s new exhibition.