Google “Native American appropriation art” and the first five pages of results or so are all about negative cases of cultural appropriation. On these pages we can read about how outsiders misuse Native American images and cultural heritage, such as the infamous feathered headdress on a lingerie clad model in a Victoria’s Secret show five years ago. Cultural appropriation, of course, continues to be a problem and something that should be addressed and discussed. However, when typing in that search term I wasn’t looking for Native Americans as victims. I wanted to read about how appropriation is used as a strategy within contemporary Native American art. I was looking for Native American artists as agents of empowerment. To find such results buried under droves of articles about how Native American iconography has been mistreated must feel like a double slap in the face. First whites steal Native cultural practices and use it in a distorted way, then this act of appropriation steals the attention away from Native artists who use appropriation as a way to symbolically fight back.

This makes it very difficult to place the aesthetic tactics of many Native American artists into proper art historical perspective, which is a shame, especially considering how significant appropriation is for many Native artists. Appropriation is, after all, a genre of contemporary art that has perhaps been the most important hub for questions concerning artistic authorship and originality and the contextual relativity of the meaning of images. It is perhaps within the Native art community that the legacy of appropriation art today finds it’s firmest stronghold. At first sight it may come as a surprise to learn how popular Andy Warhol is in this community. I can tell you that it is not because of his “Cowboy and Indian series”, but rather because of how Warhol demonstrated that the specialness of a sign – for instance a Campbell’s soup can – can be emptied by the act of repetition and how the meaning of a pre-existing image or object can be altered by placing it within a new context.

Warhol himself was not a particularly political figure, but the strategy of appropriation, of “copying” images and making them your own, has a history of political uses.

Dara Birnbaum and Sherrie Levine used appropriation to feminist ends. By repeating and recontextualizing imagery by male originators they questioned the authenticity of representations of gender. Appropriation has also been employed to question the commodity value of art and its underlying economic structures.

Even before it was a genre of art, Raphael Montanez Ortiz performed a case of appropriation aimed at exposing the misrepresentation of Native Americans. In 1957 he used a Tomahawk to chop up Anthony Mann’s western Winchester ’73. He then put the pieces back together at random, resulting in a complete scrambling and disruption of the original narrative. “Ortiz considered his shaman-like process resonant with his indigenous heritage. His destructive act also criticized media depictions of Native Americans.”

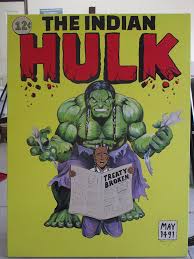

As a genre, Native American appropriation art comes across as something self-evident and completely natural. Artists are simply taking images back that were stolen from them. Artists such as Douglas Miles, Jaque Fragua, Steven Paul Judd, Ryan Singer, among many others, consider appropriation a way to take repossession of images that they have lost control over. In short, one might say that appropriation art is a means to combat cultural appropriation.

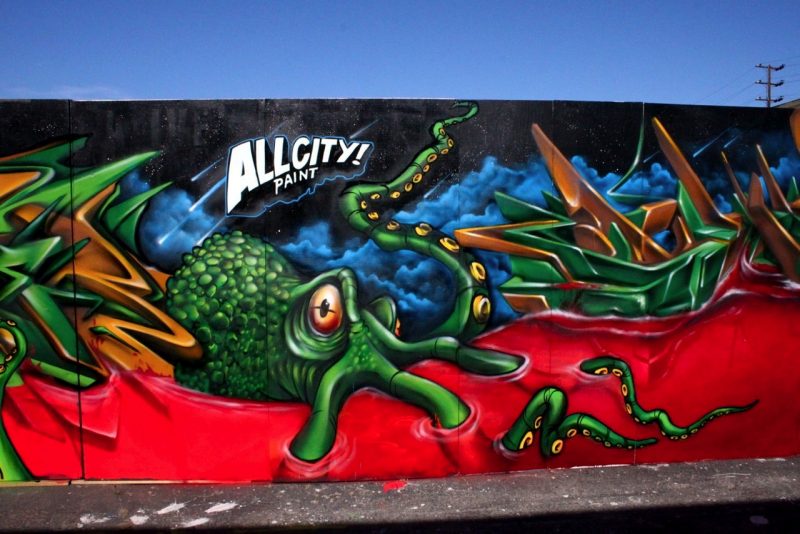

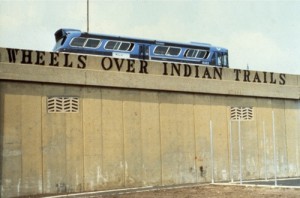

We’ve written about the importance of graffiti for contemporary Native artists many times here on the blog. In the hands of Native artists, painting with spray cans in public spaces is no petty act of vandalism but a profoundly political gesture. This is clearly demonstrated by Jaques Fragua who wrote “This Is Indian Land” in giant letters on a construction site in Downtown Los Angeles. The act of appropriation is performed in a spirit kindred to graffiti. For Native American artists it is about re-claiming what is rightfully theirs by symbolically taking back their land by illegally writing on it, or redefining images that have been made from an external point of view.

We haven’t written about Jaque Fragua on the blog before, so let’s continue on him. Besides graffiti, Fragua considers appropriation one of his artistic go-to’s. “The Big Chief” is for instance a commercial symbol that has become a recurring character throughout Fragua’s work. Fragua explains: “He’s a chief from a sign that’s near my reservation, at Big Chief Gas Station. If you’ve ever watched Breaking Bad, you’ve see that gas station. I lifted him and I’ve been putting him everywhere—he’s the Big Chief, right? When you put a mirror against another mirror, you start seeing the core of the truths.”

In another interview, Fragua explains the appeal of appropriation more in depth: ”Simply, it’s about imagery that continues to colonize us. By creating fine art out of these visuals and emphasizing the images ad nauseum, it creates the opposite effect. Sort of like Warhol’s soup cans.” Fragua thus reappropriates his culture’s iconography in a way that conceptually subverts our overconsumption of misappropriated Native American images that has turned into stereotypes.

Some critics fear that appropriation as a artistic gesture has lost some of its meaning in a time when borrowing, quoting, stealing and copying is everyday practice to the point of being ubiquitous. However, for Native American artists, appropriation simply follows the rules of the game set by a white hegemony. It is the answer to a signifying practice already put in place. As such, appropriation is important now perhaps more than ever. With a president that casually refers to people of Native American heritage as “Pocahontas”, and a culture at large that hold it’s racial stereotypes dearly, appropriation as artistic weapon offers a way to strike back. Contemporary Native American artists turn to appropriation not to be trendy or edgy but out of urgency. It opens a line of dialogue that lets Native Americans have the last word on images that they were not in charge of in the first place and thus to let the public know what they think about them.

Further reading about cultural appropriation:

https://unsettlingamerica.wordpress.com/2011/09/16/cultural-appreciation-or-cultural-appropriation/

https://jezebel.com/5959698/a-much-needed-primer-on-cultural-appropriation

http://nativeappropriations.com

About appropriation art:

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-the-art-of-copying-ten-masters-of-appropriation

https://www.thoughtco.com/appropriation-appropriation-art-183190