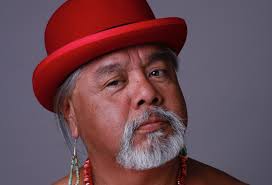

The world of performance art suffered a great loss when artist James Luna passed away at the beginning of this month. A resident of the La Jolla reservation, Luna was a highly respected figure of the California Native community. As someone who considers La Jolla and its surroundings somewhat of a second home, I have seen first hand how revered and admired Luna is in those parts. His importance, however, transcends geography and his work has been particularly relevant to recent discussions of cultural misrepresentation and appropriation. With a president who casually refers to his Native American co-workers as “Pocahontas”, the current political climate needs every strong voice of objection and protest it can summon. Luna was indeed one such voice and many of his pieces were conceived to actively disrupt the romanticized commodification of Native culture. In the performance “Take a Picture With a Real Indian”, for instance, Luna targets the gap between the popular image of Indians and Indians as actual human beings.

Luna originally staged the performance at Union Station in Washington D.C. in 1991. The performance consisted of Luna taking up a spot and proclaiming to bypassers: “Take a picture with a real Indian. Take a picture here, in Washington, D.C. on this beautiful Monday morning, on this holiday called Columbus Day. America loves to say ‘her Indians.’ America loves to see us dance for them. America likes our arts and crafts. America likes to name cars and trucks after our tribes. Take a picture with a real Indian. Take a picture here today, on this sunny day here in Washington, D.C.”

Being photographed together with strangers who saw him primarily as an object would not surprisingly take a toll on his pride and Luna would end the performance when he felt too upset or humiliated to continue.

The video above is from a more recent recreation of the performance but here too the discomfort is clearly visible. This discomfort seem to be shared by performer and participants alike. Sometimes it’s unclear why the people in the audience want to have their picture taken together with Luna. Are they clued into the motives behind the performance or do they respond to the exotic nature of the offer, as if being photographed with an Indian is an opportunity as rare as meeting a lion. Maybe the participants themselves don’t really know. And this confusion and uncertainty is testament to the success of the work. The performance opens a space for the audience to question their own reception of exotic constructs.

Luna was reportedly trained by the mythical Bas Jan Ader who disappeared at sea during the creation of one of his art pieces. Although he didn’t go to quite the same extremes as Ader, Luna did make his own body his primary artistic medium. This made Luna’s work particularly challenging. Other Native artists may have tackled the same subjects as Luna, but the fact that he used his own body lends an confrontational and physical poignancy to topics and themes that might otherwise remain confined to the intellectual realm.

Luna’s physical methods were particularly effective when he located his critique to the institutional practices of museums. In “The Artifact Piece” (performed in 1987 at the San Diego Museum of Man) Luna put his own body on display, laying it down in the museum among other historical objects. Thinking he was a lifeless object of exhibition, some visitors would touch his body and experience a slight shock upon finding it a living and breathing entity. It is one thing to verbally point out the discrepancies between the Native American as historical artifact found in museums and Native American as a living and thriving culture. But to stage this discrepancy through one’s own body is quite another thing and the piece had a huge impact among Native artistic communities.

Personally, I knew James Luna only very superficially. A few years ago James Luna reached out to me with the proposition of collaborating on something in Sweden. Nothing materialized, however, and I sadly regret that the opportunity now has passed. Among many of the artists represented by Kiva Gallery, James Luna is spoken of with the highest admiration and respect. Luna struck a rare balance of fearlessness, humour and sensitivity in his art, and for this his influence will doubtlessly live on.