There are days when you don’t have anything in particular to report – no news and no opinions. Some days you just want to write about something that makes you feel good. Something to inspire you to get off your ass and do stuff. Something in the “hell yeah!”-vein, in other words. This is one of those days. There are many things I love about Native American Art, but there is one thing in particular that keeps hold on me and it’s something that runs deeper than surface aesthetics. It is a certain attitude that shows you how powerful art can be. Art can give you a voice when other means of expression are suppressed. It is hard to find that attitude elsewhere, at least so collectively concentrated. The realization that art can show reality but also create another reality is what makes so many Native communities bubble with creativity.

The rapper Drake said in the song “Fireworks”: “from the concrete who knew that a flower would grow”, meaning that it is surprising that beauty could come from harsh circumstances. He clearly has no concept of Native Art. Or, to take an example closer to Drake’s own rap identity – New York’s graffiti culture in the late 1970s and early 80s. There is a lot about that era that reminds me of the contemporary Native art scene. That period is all about the creative ways of the disenfranchised to grow out of the concrete. Spraycan graffiti was a completely invented art form so there were no art schools to teach you how to do it. Ghetto kids were the professors and their education was on the streets where the tricks of the trade were passed from peer to peer. At the beginning there were no commercial ambitions- the practitioners had yet to find a way to monetize their art. It was just about rising above the everyday struggle by creating something beautiful and spreading it throughout the streets.

Art is empowering. It let’s you create and define your own world. When the realization of this occurs on a collective level, like with graffiti in 1970s New York, art is injected with an energy and enthusiasm that is highly intoxicating and convincing. Similarly, a lot of Native Americans today latch on to art as a source of optimism and tool for change.

I’m writing these words with one particular artist in mind: Steven Paul Judd. Few people embodies the DIY – attitude like Judd. He embarked on his artistic trajectory when trying to find some nice Native art to hang in his house. He failed to find anything that corresponded to his taste for pop art, so he simply set to work making some himself.

It is no accident that Judd has close ties to graffiti culture. But labelling Judd just a graffiti artist would be reductive. Creativity just pours out of him and into every facet and category of art. This guy is just pure inspiration, in the truest sense of the word. He has no proper education in the arts so he doesn’t always know the ”hows”, he just knows that he has to do it. And a lot of the times, Youtube tutorials will get you where you need to go. The quote in the title to this piece, of course, comes from Steven Paul Judd. And the mentality of going for it runs through his entire practice of art.

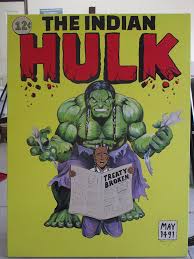

Not least it applies to his approach to historical iconography. Judd quite often uses familiar imagery but in a way as to make it more Native-centric. He uses art to create his own alternate version of pop-culture, for instance by fusing historical Native American iconography with the world of Star Wars, or by recasting superheroes such as The Hulk as Native American. Claiming your space in this way, despite what history and the powers that be say, is a deeply graffiti-like attitude.

In an interview Judd talks about his creative process in a way that seems to be representative of his energy and eagerness to get things done. Recently, Judd has been creating portraits of Sitting Bull, composed entirely out of Rubik’s Cubes. Which is like building a complicated puzzle, with smaller puzzles for pieces. The initial plan was to mount it on the wall but he finished the puzzle before he had figured out a way to fasten the cubes on the wall. So he just let the cubes lay on the floor, the art work now an installation rather than a wall piece.

If there’s a will there’s a way, I believe is the accurate motivational phrase here.

To continue in this vein of self-improvement, let us sum up by making it a rule that whenever you feel that things are just too damn hard, ask yourself: what would Steven Paul Judd do? If the conclusion you come up with is not “Okay, I think I can do that”, you’re doing it wrong.