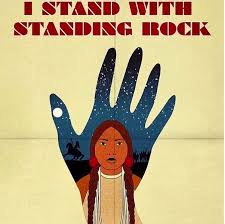

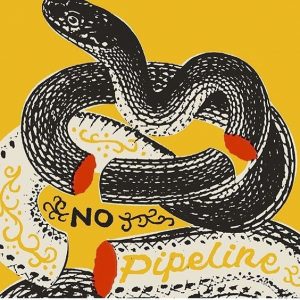

If nothing else, we can be grateful to President Trump that there is more political art and music now than we have seen in a long time. To realize that art flourishes in times when there is much too protest about you only need to scroll through your daily Instagram feed and look for Trump-related posts. The aspect of his presidency that has perhaps sparked some of the most thematically specific art concerns the pipeline in North Dakota. When Trump reversed Obama’s cancellation of the completion of the pipeline through Sioux territory, art became a central component in the protests against it. Now that the protesters have been evacuated from their camps and work has begun to finish the controversial pipeline, the artistic protests that are still being produced proves that the struggle is far from over.

One of the more effective artistic interventions into the conflict was Cannupa Hanska Luger’s mirrored shields. Using cheap masonite and adhesive mirrors, Hanska Luger crafted shields that were passed out among by the protesters. This, however, was more than an act of rearmament to match the equipment of the police who often carry shields at demonstrations. According to Hanska Luger the reflective surfaces on the shields would reveal to the policing forces the shared  humanity “underneath their uniforms—and [make them] realize that they are also on our side” (http://theartnewspaper.com/news/artist-creates-mirrored-shields-for-standing-rock-protesters/). The shields thus function as protection against bodily harm but also as a peaceful deterrent to any kind of violent confrontations.

humanity “underneath their uniforms—and [make them] realize that they are also on our side” (http://theartnewspaper.com/news/artist-creates-mirrored-shields-for-standing-rock-protesters/). The shields thus function as protection against bodily harm but also as a peaceful deterrent to any kind of violent confrontations.

The shields were also used in a performance that can be seen here: http://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/2016/12/04/hundreds-mirror-shields-used-standing-rock-art/94961662/

Cannupa Hanska Luger explains the role of the artist: “Artists, we live on the periphery. But we are the mirrors. We are the reflective points that break through a barrier.” (http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/miranda/la-et-cam-cannupa-hanska-luger-20170112-story.html)

That is the power of art in times of conflict. It is more than just a polarized opinion that can easily enough be dismissed by those who take the opposite stance. As such, it has the power to break through barriers. Here is some more art that tries to do just that.